The history of refrigerants

To effectively manage your business’s refrigerant inventory, it is helpful to understand how potent greenhouse gases became ubiquitous in the first place, and which cleaner alternatives are now available. We thought providing a bit of context on the history of refrigerants would be helpful.

Do environmentally friendly refrigerants exist?

Natural refrigerants such as ammonia and propane have been used for hundreds of years, and are among the most environmentally friendly, efficient options. When used as a refrigerant or in air conditioners, ammonia is highly effective at absorbing substantial amounts of heat from its surroundings. Propane emits less carbon monoxide than gasoline, produces fewer particles than diesel, and contains no Sulphur (a contributor to acid rain). Both have a global warming potential (GWP) between 0 and 4, a stark difference from some of the first synthetic refrigerants, which registered global warming potential (GWP) in the tens of thousands. Though they are better options from an environmental standpoint, the quest for optimal, human-safe, climate-safe refrigerants continues.

History of refrigerants

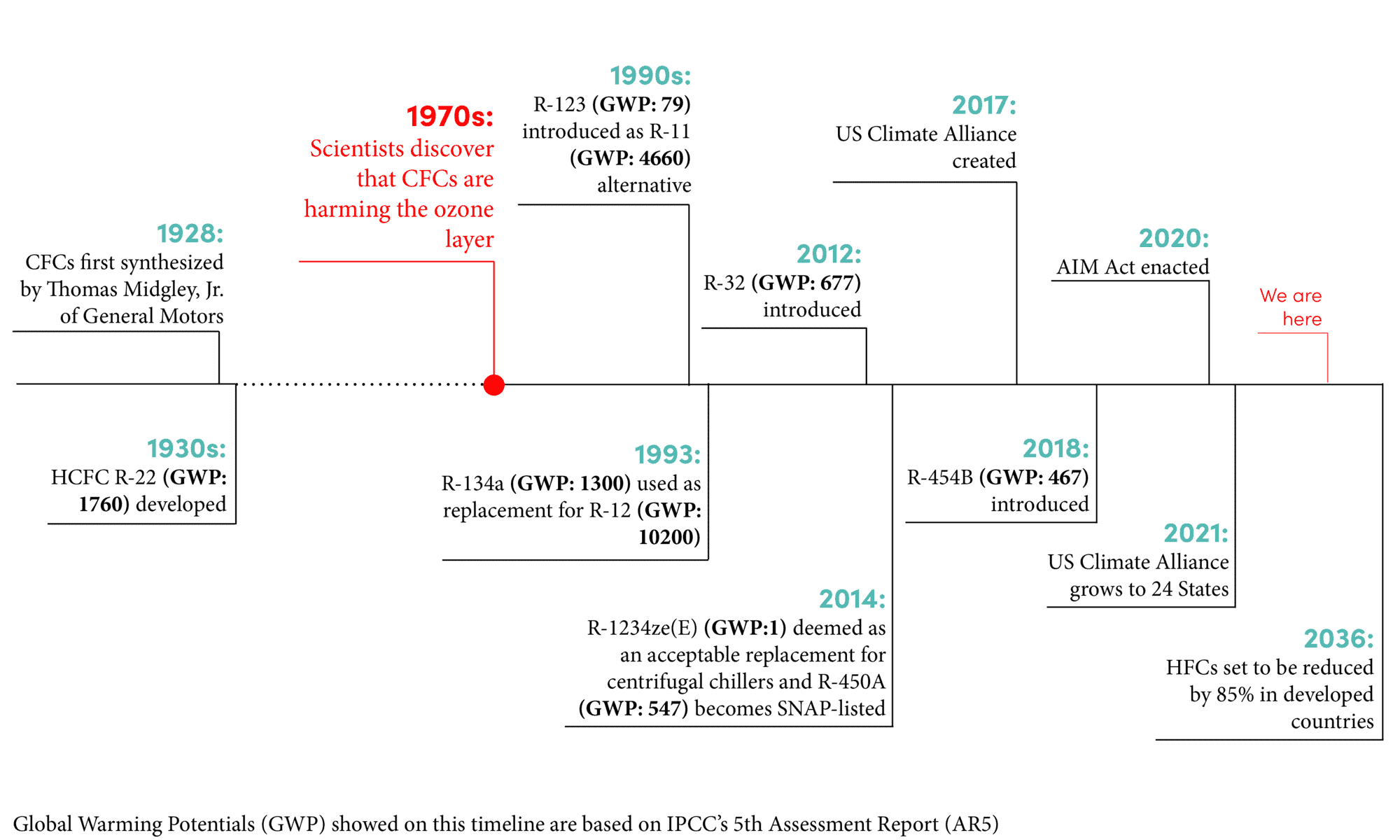

Early (pre-1900s) refrigeration was centered around the often-treacherous practice of hauling ice from frozen lakes and rivers. Safer options were sought, and the first refrigerants (including ammonia) were used, but with the advent of the use of chemicals to cool, these new contraptions were known to be a dangerous alternative, proving fatal when leaks or fires occurred. People would often place their refrigerators in their backyards, to keep the toxic chemicals at a distance. This led engineer Thomas Midgley Jr., in 1928, to develop the first synthetic refrigerant chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) R-12, or “Freon,” as a safer, non-flammable, and non-toxic solution. Following R-12’s widely marketed success, hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC) R-22 was developed, followed by others including hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) R-134a, which are still used globally in common applications like refrigerators and vehicle air conditioners.

Global efforts to mitigate

By the 1970s, scientists had discovered that the use of these CFCs and, to a lesser extent, HCFCs, were causing serious damage to the ozone layer. In 1987, 197 countries ratified the Montreal Protocol, a global agreement to phase out the production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances. CFCs R-11 and R-12 were phased out in the 1990s and replaced with the less-damaging HFCs. But these are still potent greenhouse gases, and in 2016, the Kigali Amendment was added to the Montreal Protocol.

The Amendment called for countries to cut their HFC production and consumption by more than 80 percent over the next 30 years, with staggered deadlines for different economic capacities and infrastructure. While the EU F-Gas Regulation of 2014 began phasing out HFCs on an accelerated schedule in EU countries, under the Kigali Amendment, other developed nations were not required to begin until 2019 (or later), and developing nations were given even more time. The U.S. government did not enact a phase down or ratify the Kigali Amendment until 2022, and thus has less time remaining to meet their mandate of an 85% phase down by 2036.

The US Climate Alliance, a bipartisan group now numbering 25 U.S. governors, has committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions (including refrigerants) in line with the goals set by the 2015 Paris Agreement, wherein 196 governments agreed to work to keep the world’s average temperature well below rising to 2°C above what it had been before the Industrial Revolution.

Lingering threats, emergent solutions

These efforts are essential to meeting longer term mitigation goals, but near-term threats also require immediate action. While HFCs are still in the midst of being phased out, the costs of maintaining the systems they require will continue to rise if they are not replaced by a viable alternative. And though the phase outs have been effective in halting production of new toxic refrigerants, they do not yet include mandates to destroy the vast stores that already exist. As a result, they are still in use on a global scale, or are sitting in aging storage containers that will at some point decay. Once these gases, which have a GWP much higher than carbon dioxide, leak into the atmosphere, there will be no way to remove them.

As the process of destroying and phasing out toxic refrigerants continues, a larger push is being made to revert to the use of natural refrigerants (such as hydrofluoroolefins [HFO]) that have been developed to have a lower GWP and no ozone-depleting potential. With these measures, accompanied by advancements in technology and more robust safety measures, industries are adopting a future-thinking climate perspective and are increasingly able to commit to sustainable, cost-effective practices.