This credit card has a superpower.

(It destroys greenhouse gases.)

Saving the planet never paid this well before.

Every dollar spent with the Climate Impact Card destroys two pounds of greenhouse gases – while paying you 3% cash back.

Just think — you can get the extras you expect from a credit card, plus the environmental impact you didn’t think you could make.

Cash Back when you shop

Destroy greenhouse gases with every purchase

Fraud protection, enhanced security, and more

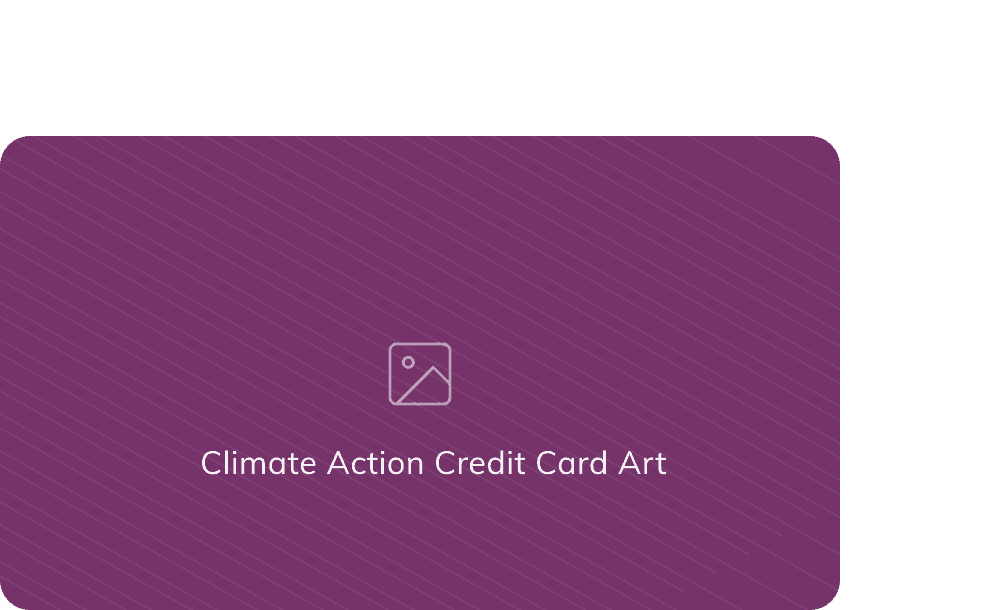

How it Works

Each purchase with the Climate Impact Card helps fund Tradewater, an organization with a mission to improve our environment by removing dangerous greenhouse gases. Every day, Tradewater representatives seek out, collect, and destroy highly potent CFC refrigerants from around the globe.

Every time you use the Climate Impact Card, we’re able to destroy more greenhouse gas – and you get 3% cash back.

Make the world better while making your world better.

The Climate Impact Card directly removes greenhouse gas with every use. To date Tradewater has prevented the equivalent of over 4.6 million tons of carbon dioxide from being released to the atmosphere since 2013—at no cost to cardholders.

Together we’re making a difference.

The Climate Impact Card has joined Intuit in its commitment to climate-positive action. Intuit’s Climate Marketplace is a significant effort with great impact, and we’re very proud to participate because we share a commitment to making our world more sustainable.

We’re all doing our part - and now you can, too.

© Copyright Tradewater 2021

Tradewater generates carbon offset credits by collecting and permanently destroying harmful refrigerant gases (HFG) through a safe, verifiable process. If not destroyed, these HFGs would eventually be released into the atmosphere.

Permanence

Emission reductions are considered permanent if they are not reversible. In some projects, such as forestry or soil preservation, carbon offset credits are issued based upon the volume of CO2 that will be sequestered over future decades—but human actions and natural processes such as forest fires, disease, and soil tillage can disrupt those projects. When that happens, the emission reductions claimed by the project are reversed.

The destruction of halocarbon does not carry this risk. All destruction activities in Tradewater’s projects are conducted pursuant to the Montreal Protocol , which requires “a destruction process” that “results in the permanent transformation, or decomposition of all or a significant portion of such substances.” Specifically, the destruction facilities Tradewater uses must meet or exceed the recommendations of the UN Technology & Economic Assessment Panel , which approves certain technologies to destroy halocarbons, including the requirement that the technology achieve a 99.99% or higher “destruction and removal efficiency.” Simply put, this means that Tradewater’s technologies ensure that over 99.99% of the chemicals are permanently destroyed. During the destruction process, a continuous emission monitoring system is used to ensure full destruction of the ODS collected.

Accuracy

Some carbon offset projects necessarily rely on estimations or assumptions when calculating the emission reductions from project activities. Forestry projects, where developers make assumptions about the carbon that will be sequestered over future decades if trees are conserved, are a perfect example. Such projects sometimes result in an overestimation of the environmental benefit of the project.

Tradewater’s halocarbon projects avoid the issue of overestimation by consistently conducting extremely precise testing and measurement of the amount of refrigerant destroyed in each project.

Additionality

It is a basic requirement of all carbon offset projects that the underlying project activities are additional. “Additional” means that the projects would not happen in the absence of a carbon market. Tradewater’s halocarbon projects simply would not happen – and the gases would be left to escape into the atmosphere – without the sale of the resulting carbon offset credits. This is because there is no mandate to collect and destroy these gases. It is still permissible to buy, sell, and use halocarbons that were produced before the ban. There are other reasons halocarbon destruction projects are additional:

- There are no incentives or financial mechanisms to encourage halocarbon destruction. According to the International Energy Agency and United Nations Environment Program, “there is rarely funding nor incentive” to recover and destroy ozone depleting substances in storage tanks and discarded equipment. And collecting, transporting, and destroying halocarbons is time-intensive and expensive. The burden to collect and destroy these gases therefore remains prohibitive outside of carbon offset markets—meaning that if organizations like Tradewater do not do this work, nobody else will.

- Countries are not focused on the need to collect and destroy halocarbons. The Montreal Protocol has been celebrated as a success because of its production ban. This success, however, ignores the legacy gases produced before the ban and is a blind spot for government regulators. In the U.S., for example, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) developed a Vintaging Model in the 1990s to estimate the quantify of ozone depleting substances left in circulation. Based on the inputs and assumptions put into the model, the EPA predicted that no CFCs would be available for recovery beyond 2020 in the United States. But this prediction did not prove accurate. Tradewater has collected and destroyed more than 1.5 million pounds of CFCs globally in recent years and continues to identify thousands of pounds per week.

- International carbon accounting standards do not require corporations to measure or track emissions tied to halocarbons, and refrigerants are specifically excluded from Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) commitments. These commitments derive from emissions reporting under the GHG Protocol, which requires companies to report on emissions only from new generation refrigerants, such as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), but does not establish any obligation to report inventories or emissions of refrigerants still in use, such as CFCs and HCFCs. All these factors combine to make Tradewater’s carbon offset projects highly additional. As Giving Green, an initiative of IDinsight, concluded: “Tradewater would not exist without the offset market, so this element of additionality is clearly achieved.” The case for additionality is not so clear for some other project types, such as forestry and landfill gas carbon projects. For example, some forests are already being conserved for their beauty, or for use as parks, and generate carbon offset credits only because those conservation efforts do not yet have full formal protection in place to avoid deforestation in the future. Similarly, methane from landfills can be used to make electricity or captured as compressed natural gas, thereby creating additional revenue streams to support the activities, beyond the sale of carbon credits.